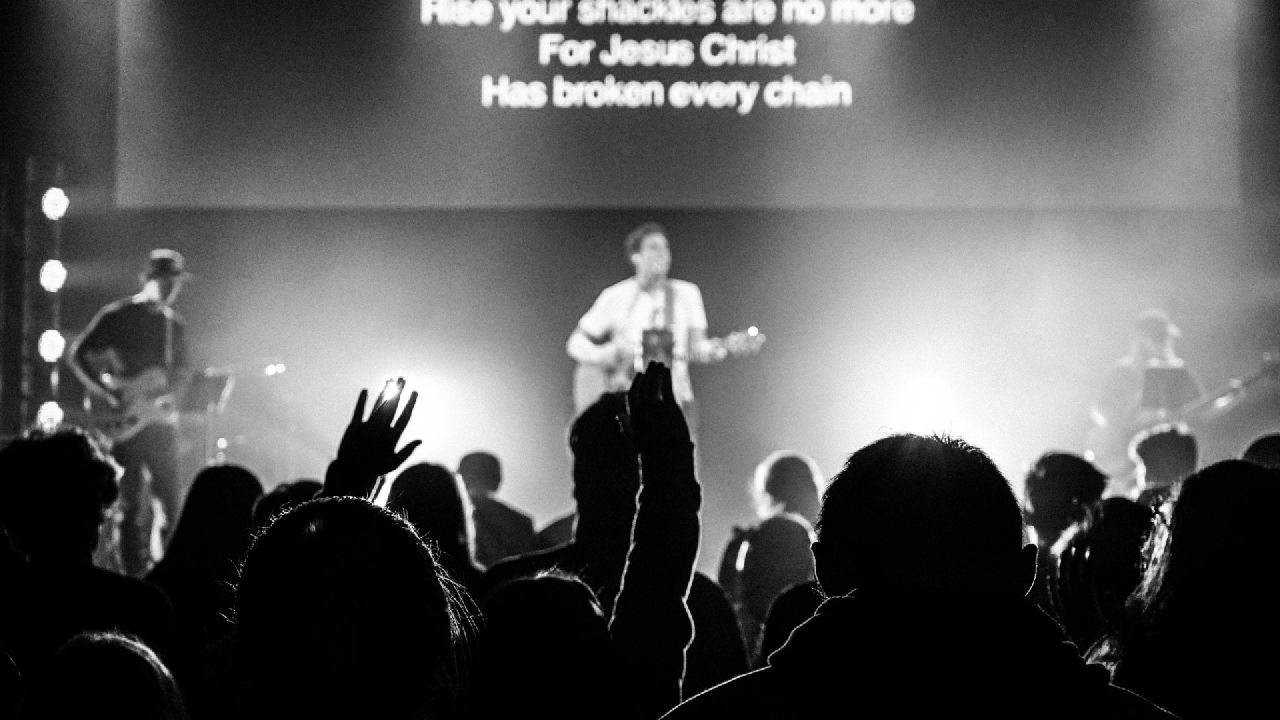

I suspect you’ve seen this in church before: The worship band begins to play a well-known hymn. The congregation confidently joins in. Then the band creatively adds a little unexpected extra space between stanzas, and a few people get caught singing loudly through the silence. Everyone is immediately on guard, hesitant. Sometimes we recover, but as the creative liberties increase, the number of people worshiping steadily decreases. We wait quietly, listening, watching the band worship as our limited time together slips away.

The art of leading congregational worship is being lost, and I think we are all poorer for it. James K.A. Smith sums up very well my thoughts on this in his “An Open Letter to Praise Bands”:

1. If we, the congregation, can’t hear ourselves, it’s not worship. Christian worship is not a concert. In a concert (a particular “form of performance”), we often expect to be overwhelmed by sound, particularly in certain styles of music. In a concert, we come to expect that weird sort of sensory deprivation that happens from sensory overload, when the pounding of the bass on our chest and the wash of music over the crowd leaves us with the rush of a certain aural vertigo. And there’s nothing wrong with concerts! It’s just that Christian worship is not a concert. Christian worship is a collective, communal, congregational practice—and the gathered sound and harmony of a congregation singing as one is integral to the practice of worship. It is a way of “performing” the reality that, in Christ, we are one body. But that requires that we actually be able to hear ourselves, and hear our sisters and brothers singing alongside us. When the amped sound of the praise band overwhelms congregational voices, we can’t hear ourselves sing—so we lose that communal aspect of the congregation and are encouraged to effectively become “private,” passive worshipers.

2. If we, the congregation, can’t sing along, it’s not worship. In other forms of musical performance, musicians and bands will want to improvise and “be creative,” offering new renditions and exhibiting their virtuosity with all sorts of different trills and pauses and improvisations on the received tune. Again, that can be a delightful aspect of a concert, but in Christian worship it just means that we, the congregation, can’t sing along. And so your virtuosity gives rise to our passivity; your creativity simply encourages our silence. And while you may be worshiping with your creativity, the same creativity actually shuts down congregational song.

Worship leaders, if you look out over the congregation and you see that we are not singing with you, something has gone wrong. Are you jamming alone up there for extended periods of time? Are you changing well-known melodies just enough to surprise us and make us hesitant to sing out, and/or adding flair that we can’t follow? Are you choosing soloistic songs with complicated melodies rather than musically simple ones designed for group singing?

The best thing you can do is to consider carefully the purpose of your role as you make your decisions for each service. You have the noble position of enabling all of us to draw together as one before God to express our love and honor through a powerful medium. If you can keep that goal in mind—the goal of enabling the congregation to worship—and ruthlessly shed anything, however musically tempting, that doesn’t advance that goal, we will thank you.

[HT: Justin Taylor]