When it comes to talking with Muslims, I like to point them to Jesus—his life and his message—described in the Gospels. Why? Muslims must believe in Jesus (as a prophet) and in the revelation given to him (the Quran calls this revelation the Injil). My approach is simple and contains four steps:

- Ask a key question.

- Point to Jesus in the Gospels.

- Use a tactic if necessary.

- Go back to Jesus in the Gospels.

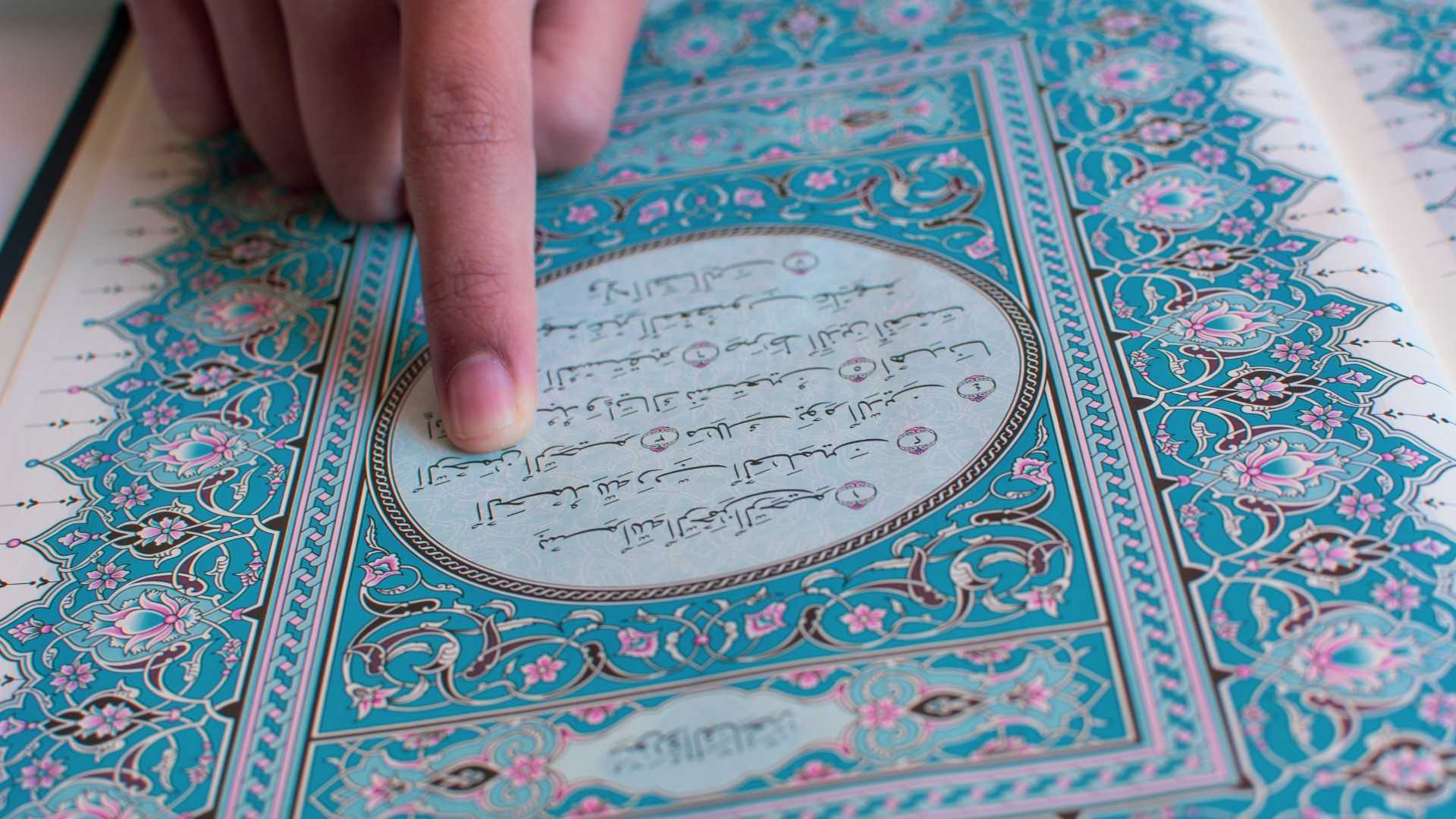

Before I unpack these four steps, a quick clarification is in order. The Quran teaches that Allah gave each of his prophets divine revelation in the form of a book. An angel dictated the contents of these books to his prophets: the Torah (Taurat) to Moses, the Psalms (Zabbur) to David, the Gospel (Injil) to Jesus, and the Quran to Mohammed. Most Muslims believe the Injil is a single book (like the Quran) given to Jesus, but there is no historical evidence whatsoever that Jesus received or was given any document. When the Quran refers to the Injil that the Christians had in the 7th century (that’s when the Quran was written), the only Gospels the Christians possessed were Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. Therefore, the Quran’s reference to the Injil is most likely a reference to the four Gospels. With that background information, let’s unpack these four steps.

Ask a Key Question

First, ask a key question. One of my favorite questions to ask a Muslim is, “Are you 100% certain you are going to Heaven?” To the best of my memory, I’ve never had a Muslim answer yes. Why? According to Islam, whether a person goes to Heaven or not is determined by Allah based, in part, on the number (and weight) of the good and bad deeds they commit in their lifetime. Since no Muslim knows what their deeds will amount to, my follow-up question is, “Would you like to have 100% certainty?” Most Muslims will either want that level of certainty or, more likely, just be curious as to what I’ll say next.

Point to Jesus in the Gospels

Second, point them to Jesus in the Gospels. Specifically, I tell my Muslim friend to read John 3:16–18 (or I read it with them).

For God so loved the world, that He gave His only begotten Son, that whoever believes in Him shall not perish, but have eternal life. For God did not send the Son into the world to judge the world, but that the world might be saved through Him. He who believes in Him is not judged; he who does not believe has been judged already, because he has not believed in the name of the only begotten Son of God.

This passage is a good summary of the message of reconciliation that God offers sinful man. In other words, it’s a good summary of the gospel message. It gives anyone who “believes in [Jesus]” the confidence that he “shall not perish, but have eternal life.” I use this passage for several strategic reasons. First, it’s easy for a Christian to remember the reference of this passage because it’s connected to the most famous verse in the Bible (John 3:16). You just need to remember to add two additional verses. Second, it’s found in one of the Gospels of the Bible. This is significant because the Quran identifies the Gospels (the Injil) as revelation from Allah. According to the six articles of faith in Islam, Muslims must believe in all of God’s books, one of which is the Injil. Third, the passage is a quote from Jesus. Muslims are required to believe in all the prophets identified in the Quran, and Jesus (the Quran calls him Isa) is one of them.

If your Muslim friend is willing to receive Jesus’ message and perhaps learn more about him, then you can invite them to read more of John or the other Gospels. This is good news since you were successful at presenting the message of reconciliation from the lips of Jesus. Unfortunately, there is also a good chance your Muslim friend will reject what Jesus says in John because of a very common objection.

Use a Tactic if Necessary

Third, use a tactic if necessary. The most likely objection you’ll get from your Muslim friend is, “The Bible is corrupted.” In other words, Muslims can’t trust what is said in John 3:16–18 because although the Gospels (Injil) are a revelation from Allah, they have since been corrupted.

I use a tactic to undermine this objection, because until you do, your Muslim friend will not heed Jesus’ message from John. The tactic leverages a Muslim’s commitment to the Quran, their highest authority. The goal is to show that the Quran teaches the Gospels (Injil) have not been corrupted but are trustworthy. The tactic incorporates three things the Quran affirms about the Gospels (Injil):

- The Gospels (Injil) are a divine revelation from Allah (surah 3:3, 2:136, 5:46).

- The Gospels (Injil) were available in Mohammed’s day (7th century) when the Quran was being “revealed” (surah 4:47, 5:47, 5:68, 7:157).

- The Gospels (Injil) are authoritative—they should be believed and obeyed (surah 5:68, 4:136, 29:46).

In other words, the Quran teaches that Allah sent Jesus the Gospels (Injil) and also that they were available to Christians and Muslims in the 7th century. Why, then, would Allah command people to obey the Gospels (Injil) if they were corrupted? That wouldn’t make sense. What you are trying to demonstrate to your Muslim friend is that their claim that the Gospels (Injil) are corrupted is at odds with what the Quran—their highest authority—teaches.

The Gospels (Injil) couldn’t have been corrupted after the Quran either. There exist copies of the entire Bible—Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Vaticanus—that date a few hundred years before the Quran was written. The copies of the Bibles we have today are consistent with those manuscripts.

If your Muslim friend acknowledges your point and relents on their claim that the Gospels in the New Testament are corrupted, then this will open up an opportunity for them to learn about Jesus from the passage in John.

Go Back to Jesus in the Gospels

Fourth, go back to Jesus in the Gospels. Now you can go back to John and resume telling your friend about Jesus, his mission, and the message of reconciliation. At that point, you’ve accomplished an important goal in sharing God’s offer of a pardon with your Muslim friend.

Some people wonder if a conversation can really be that simple. No. I’m not claiming every conversation goes in this direction, or that it’s always simple, or that it always—or even usually—works. I’m merely laying out the approach I take. I want to get to the gospel message, and I’ve found this method makes it possible quite often.